The year was 2012.

I was working with a client and I turned her business around with a simple client getting technique that works every time.

She was so impressed she insisted on doing something special for me.

“Is there anything you want?” She asked.

“Please get me a copy of The Brilliance Breakthrough by Eugene M. Schwartz.”

Two weeks later she emailed me a pdf of this rare book.

Get this.

She paid $5 for it.

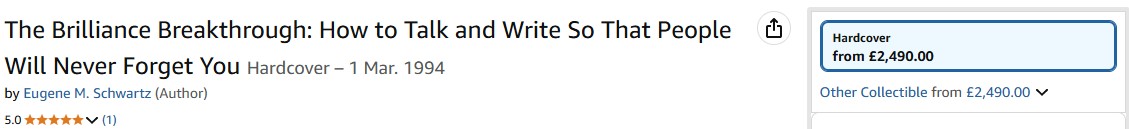

If you went on to Amazon today this is what you’ll find.

In 2012 copywriters (who should have known better) we slating this book.

Making out it wasn’t useful.

But I knew different.

I had seen the 90-minute video on May 11 1994, when Eugene shared his most precious secrets and at the end of the video he gave a copy of his latest book to every copywriter at Rodale Press.

In case you don’t know Rodale press is a high flying direct response company.

https://youtu.be/BBnmlj03R_A?si=RBmBtx8SrNtTQqhU

I guessed that if Eugene gave this book away to these to copywriters it had to be special.

He wrote it almost 30 years after he wrote Breakthrough Advertising.

Several courses have been given on that book, but none (to my knowledge) on this book.

Other than a look at the first four chapters by the A level copywriter Daniel Levis.

So, I’m going to change all that.

In this article I’m going way down the rabbit hole of this outstanding book.

Before I do you need to know how to get a copy of this book at far less than the Amazon cost.

https://brilliancebreakthroughbook.com/

Fair warning:

This is NOT an easy book to read.

In fact, it may well be the most difficult book you’ll ever read.

But, like Breakthrough Advertising it will be the most rewarding book you’ll ever read.

A New Look at The Brilliance Breakthrough.

Reading through these different angles on Schwartz’s work, I see something remarkable happening beneath the surface of his methods.

His principles tap into how our minds actually see and connect ideas.

Your Brain’s Hidden Machinery.

Picture this: Your reader’s mind processing your words.

Neurons firing.

Images forming.

When Schwartz talks about cognitive efficiency, he shows us that readers visualise as they read.

They turn your words into mental pictures.

A psychology professor I know explained how our brains chunk information.

Not into words.

Into images.

When your sentence matches these natural chunks, understanding flows effortlessly.

When it doesn’t, the mind struggles, strains, stops.

This explains why supposedly “simple” bullet points sometimes exhaust readers while rich, image-filled paragraphs carry them forward without effort.

The Invisible Edit.

Film editors cut footage not by formula but by feeling—by the natural rhythm of human attention.

They know viewers don’t watch cuts.

They watch the story unfolding between cuts.

Similarly, Schwartz shows us that readers don’t consume words.

They absorb the images that appear between them.

I watched this happen during a client test last month.

The version with explicit benefits fell flat.

But the version that created gaps—spaces for readers to generate their own images—pulled response rates up by 41%.

The power lived not in what we showed but in what readers saw for themselves.

The Empty Space Between Words.

Eastern philosophers understand something most Western writers miss.

True power emerges not from filling space but from creating it.

Imagine a Japanese garden.

The rocks matter.

But the space between rocks creates the effect.

Schwartz applies this wisdom to writing.

When he suggests “dropping off final images,” he invites readers into that space between words.

Words don’t persuade.

The pictures they create persuade.

And sometimes, the most vivid pictures form in the silence after your sentence ends.

The Mind’s Hidden Patterns.

Before NLP became a marketing buzzword, Schwartz discovered patterns that bypass conscious resistance.

Not through manipulation.

Through alignment with how we naturally process information.

He found that certain word structures create more than ideas.

They create experiences.

When he arranges words to form embedded commands, he’s not adding technique to writing.

He’s removing barriers between reader and meaning.

The Ancient Attention Machine.

Our brains evolved in dangerous landscapes where noticing differences meant survival.

Sameness disappeared from awareness.

Contrast commanded attention.

When Schwartz emphasizes contrast, he’s not creating an artificial technique.

He’s accessing the primitive machinery of human attention.

We literally cannot help but notice differences.

Our neural circuitry demands it.

The ancient hunters in our ancestral past survived by noticing movement against stillness, colour against camouflage.

Today, our eyes still jump to contrasts before we consciously decide to look.

Looking through these windows into Schwartz’s work, I see beyond techniques.

I see principles embedded in the fabric of human perception itself.

His approach doesn’t fight against how minds work.

It flows with the current of natural understanding.

For my own writing, this changes everything.

I now see that my words matter less than the pictures they create.

My carefully crafted sentences matter less than the gaps between them where meaning actually forms.

Have you noticed how your mind naturally creates images as you read?

Those aren’t just mental side effects.

They’re the entire point of communication.

Now Let’s Explore Part One of The Brilliance Breakthrough Chapter by Chapter.

Chapter 1.

The training introduces a simplified approach to grammar with just two main parts:

- Picture Words (or Image Words) – words that carry built-in pictures or images that can stand alone and be visualised

- Connecting Words (or Relation Words) – words that have no built-in pictures and only show how Picture Words relate to each other

This approach rejects traditional grammar categories (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.) in favour of this simpler framework that focuses on whether words create images or connect those images together.

Chapter 2.

This chapter explains how to combine Picture Words and Connecting Words to form effective sentences. Key points include:

1: A sentence is “as much of your thought as you can effectively give the other person at one time”

2: The process of building sentences:

-

- Choose Picture Words to convey your meaning

- Add appropriate Connecting Words to show relationships

- Arrange them in an order that can be easily understood

3: Types of Connecting Words and their functions:

-

- Space connectors (in, on, over, under)

- Time connectors (before, after, when)

- Cause-and-effect connectors (because, since, if)

- Identity connectors (is, are, was, were)

- Pointer connectors (the, that, this)

- Road-sign connectors (and, but, however)

4: The importance of not overloading sentences with too many details, which can make them confusing.

Chapter 3.

This chapter focuses on how to build understanding into every sentence by explaining how the human mind processes language.

Key points include:

1: Understanding is image-sharing – the mind translates words into images, not memorising the exact words

2: Two fundamental problems when writing sentences:

-

- The reader’s mind can only retain a limited number of words at once

- To file away an image, the mind needs to see it completely

3: Three important rules for clear, understandable sentences:

-

- Combine Picture Words and Connecting Words into complete images

- Make each image complete in as few words as possible (ideally under 10 words)

- Link multiple images with Connectors that should appear near the front of each new image

4: Avoid common mistakes:

-

- Don’t overload sentences with too many images (more than 2-3 can be difficult)

- Don’t let one image block or interrupt another before it’s complete

- Don’t leave images incomplete

5: Some Connecting Words automatically signal an open-ended structure that requires completion (when, if, until, because)

The chapter emphasises that the goal is always understanding – ensuring your reader can translate your words into the same images you intended, without struggle or confusion.

Chapter 4.

This chapter explains how to link sentences together into a coherent flow of thought. Key points include:

1: Three types of sentence Connectors:

a) Linking Connectors – words that show how one sentence relates to another:

-

- “And then” (shows continuation)

- “Because” (shows cause and effect)

- “But” (shows contradiction)

- “Therefore,” “however,” “so,” “in fact,” etc.

b) Condensing Connectors – words that condense the thought in the first sentence into a single word carried into the second:

-

- Pronouns (he, she, it, they)

- This, that, these, those

- One, both, which, such

- Can also form linking phrases (“In this way”)

c) Non-word Connectors:

-

- Punctuation marks (colon, question mark)

- Sentence structure (repetition, expected patterns)

2: The fundamental rule: “Each sentence after the first must have a Connector in it that links it up to the sentence before. And that Connector should be as close to the front of the second sentence as possible.”

3: The importance of elaboration – developing a core thought across multiple sentences using Connectors to maintain continuity

4: How sentence structure expectations allow readers to understand incomplete sentences based on pattern recognition

This approach creates a “road map” for readers to follow your thought process without confusion or mental strain.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Chapter 5.

This chapter focuses on choosing the right length for sentences, with these key points:

1: A sentence only needs to be understood at the particular moment it appears within your flow of thought

2: The fundamental rule: “Each of your sentences needs to have only enough words in it to be understood in the flow of your thought. And no more. Only enough to be understood.”

3: Sentences derive meaning from:

-

- Their own words

- The sentences that came before them

- The overall flow of though

4: A good sentence can be as short as one word (“Yes,” “No,” “None”) if the preceding context makes its meaning clear

5: Two operating rules for sentence length:

-

- Each sentence needs only enough words to be understood in the flow of thought

- Each sentence after the first must have a Connector linking it to the sentence before

6: The flexibility to vary sentence length gives writers tools for clarity, emphasis, and variety

This approach liberates writers from rigid sentence structure rules and focuses on what truly matters: being understood in the moment of reading.

Chapter 6.

This chapter focuses on writing simply so anyone can understand even complicated thoughts. Key points include:

1: The basic rule of writing simply: “To write simply, build a sentence that states that thought in the fewest possible words, and with the greatest number of Connectors.”

2: Simplicity is a ratio between total words and Connecting Words – more Connectors relative to total words creates greater simplicity

3: A troubleshooting rule: When Picture Words are overloaded (trying to serve in two word-pictures at once), break the sentence at that word and repeat it in the next sentence with proper Connectors

4: Four causes of difficulty:

-

- Misuse of Connectors (not enough or wrong ones)

- Overloading Picture Words

- Illogical order of thoughts

- Leaving out necessary facts

5: Nine simplification structures:

-

- Normal sentence structure (actor-action-object)

- Expansion of normal sentence structure

- Repetition of key phrases

- Dependent sentence structure (if-then, when-then)

- Number order (first, second, third)

- Time order (then, next, after)

- Space order (describing in visual sequence)

- Forward-signaling (telling reader what’s coming)

- Summarization (recapping what was covered)

The chapter provides a systematic approach to simplifying complex thoughts by breaking them into smaller pieces, connecting them properly, and arranging them in logical order.

Chapter 7.

This chapter focuses on avoiding monotony while maintaining simplicity in writing. Key points include:

1: The potential problem: Simplicity can lead to monotony through too many short, similarly structured sentences

2: Two main solutions to avoid monotony:

a) Variety – purposely changing the length and structure of sentences

-

- Various sentence structures (normal, dependent, expanded)

- Varying sentence length (from one word to many)

- Using multi-word images in different positions

- Combining simple sentences with basic connectors (and, but)

b) Emphasis – making certain thoughts stand out

-

- Pointing out (italicizing, forward-signaling, summation)

- Repetition of important words or phrases

- Shortening sentences beyond normal simplicity needs

3: The fundamental rule: “The simpler the thought, the longer the sentence that can still be instantly understood”

4: Balance is essential: Simplicity must always take priority over variety

-

- If a reader must stop to figure out meaning, the sentence is too long

- You can test this by leaving your writing for a day and returning to it

5: These techniques together provide nearly infinite sentence variations while maintaining immediate understanding

The chapter shows how writers can create engaging, varied prose while still ensuring every sentence is instantly comprehensible to readers.

Chapter 8.

This chapter focuses on writing clearly to avoid misinterpretation. Key points include:

1: The distinction between simplicity and clarity:

-

- Simplicity: When relationships between images are immediately understood

- Clarity: When Picture Words have only one possible meaning in their context

2: Definition of clarity: “A Picture Word, or phrase, is clear when it has only one possible meaning in the sentence in which it is used.”

3: Six types of ambiguity and how to correct them:

a) Incomplete Picture Words

-

- Example: “When a boy, my father gave me his watch.”

- Solution: Fill out the image (“When I was a boy…”)

b) Picture Words with multiple interpretations

-

- Example: “Your royalty will be 10% of the price of the book.”

- Solution: Add extra words to specify exactly which meaning (“price of the book to the customer in the store”)

c) Wrong Connector creating misinterpretation

-

- Example: “Would you like to sweep the floor with me?”

- Solution: Replace problematic words (“Would you like to help me sweep the floor?”)

d) Misplaced Picture Words or phrases

-

- Example: “Mrs. Jones was burned while cooking her husband’s supper in a terrible manner.”

- Solution: Place details close to the main image they modify

e) Unclear condensing Connector reference

-

- Example: “There are four different ways these mistakes may confuse your readers. They may obscure…”

- Solution: Repeat the original image to clarify the reference

f) Condensing Connector too far from its prime image

-

- Solution: Replace the connector with the original image

4: Three-step process to eliminate ambiguity:

-

- Write sentences making them as simple and clear as possible

- Leave them for a while (ideally overnight)

- Return and reread them to catch unintended double meanings

The chapter emphasizes that both simplicity and clarity are necessary for complete understanding, and shows how to systematically eliminate the common causes of misinterpretation.

Chapter 9.

This chapter explains how to deliberately use multiple meanings of words to create various literary effects. Key points include:

1: Introduction of “Pivot Words” – words with multiple meanings that can be strategically used for stylistic effects

2: Types of deliberate double meanings:

a) Wit – humorous change in a Pivot Word from one meaning to another in mid-image

-

- Example: “I can’t wait to get out of these wet clothes, and into a dry martini.”

- The word “dry” shifts meanings unexpectedly, creating humour

b) Pun – replacing a word with another that sounds similar but has a different meaning

-

- Example: “Thanks for the mammaries” (instead of “memories”)

- Creates humour through the contrast between the two meanings

c) Metaphor/Symbolism/Allegory – building two mutually reinforcing meanings

-

- Metaphor: Single word with expanded meaning (“The ship ploughed ahead”)

- Symbolism: Multiple words creating reinforcing images (“You shall not crucify mankind on a cross of gold”)

- Allegory: Extended symbolism throughout an entire work

d) Suspense – planned ambiguity that deliberately leaves readers uncertain

-

- Example: “Don’t turn around or I’ll blow off your head.”

- Creates tension that pulls readers forward

3: The progression from grammar to literature:

-

- The same principles that create clear sentences can create effective literary works

- These techniques “add spice” to communication while maintaining overall clarity

The chapter shows how understanding the clarity principle allows writers to deliberately manipulate meaning for artistic and persuasive purposes, rather than merely avoiding ambiguity.

Chapter 10.

This chapter focuses on elaboration – how to develop a flow of thought from sentence to sentence. Key points include:

1: Elaboration process:

-

- Choose a core idea

- Tell your listener all necessary details about it

- Connect that core idea to the next core idea

2: Paragraphs and focus:

-

- A paragraph should contain only one core idea and its elaboration

- When shifting from one core idea to another (changing focus), begin a new paragraph

- Like sentences, paragraphs have an upper limit but can be varied for simplicity, emphasis, and style

3: Thirteen elaboration structures:

a) Narrative sequence – actions following one after another in time

b) Reasons-why – motives for actions or reasons something is true

c) Causes for an event – objective factors leading to an occurrence

d) Effects of an event – what happened as a result

e) How an event unfolds – the surface appearance of an event as it happens

f) Contrast – showing differences between core ideas

g) Example – moving from general to specific

h) Documentation – bringing in proof (quotations, statistics)

i) Instruction – teaching steps to complete a task

j) Explanation – showing how something works

k) Definition – introducing the new in terms of the familiar

l) Definition by comparison – “A is like B”

m) Logic – working out conclusions from premises

4: The flexibility of these structures:

-

- These are opportunities, not rigid rules

- Can be combined and blended as needed

- Eventually become reflexive rather than conscious

The chapter emphasizes that these structures provide tools for organizing thought, but the writer remains free to adapt them to their specific communication needs.

Now Let’s Explore Part Two of The Brilliance Breakthrough Chapter by Chapter.

Chapter 11.

This chapter introduces Part Two of the book (“Brilliance Tools”) and explains how to make your communication more memorable and impactful. Key points include:

1: The importance of how you say something, not just what you say:

-

- Bland statements are forgettable

- The same thought expressed with “punch” becomes memorable and quotable

2: Example of the difference:

-

- Forgettable: “I think that this country is running downhill, and things are getting worse every day.”

- Memorable: “There has been a lot of progress during my lifetime, but I’m afraid it’s headed in the wrong direction.”

3: The discovery of rules that make “punchy statements” work:

-

- These are the same rules natural-born “phrase-makers” use unconsciously

- Now they can be used deliberately by anyone

4: The basic technique introduced:

-

- Create deliberate double meanings in your statements

- The example uses “progress” with a twist – setting up one meaning then subverting it

5: The fundamental rule:

-

- “Set up a double meaning in the first part of the sentence, and exploit it in the second!”

The chapter serves as an introduction to the second part of the book, which will explore how to apply the clarity principles from Part One in reverse – deliberately creating double meanings for impact rather than eliminating them for clarity.

Chapter 12.

This chapter explains the basic rule underlying all punchy statements, focusing on the epigram. Key points include:

1: Definition of an epigram:

“An epigram is a single sentence, of at least two parts, which by the way they verbally work together, make the content twice as strong as it ordinarily would be.”

2: Characteristics of effective epigrams:

-

- They are single sentences (“one-liners”)

- They are necessarily short

- They must be simple

- They require at least two parts: one to set up the punch, one to deliver it

3: The fundamental mechanism: CONTRAST

“Epigrams work by contrast!”

4: Three main types of contrast:

a) Contrast between two words with opposite meanings

-

- Example: “He who praises everybody praises nobody.” (Samuel Johnson)

- Structure: everybody-nobody

b) Contrast between two opposite meanings of the same word

-

- Example: “Last night, in Hamlet, Mr. S played the king as though he expected someone to play the ace.”

- Structure: play (a role) – play (a card)

c) Contrast between the conventional meaning of a word and a new opposite meaning

-

- Example: “There is always an easy solution to every human problem — neat, plausible, and wrong.” (H.L. Mencken)

- Structure: (solution = right answer) – wrong answer

5: The process of creating epigrams:

-

- Use search-commands to tell your brain where to look

- The primary search-command: “Where can I use CONTRAST here?”

- With practice, this process becomes automatic

The chapter emphasizes that creating impactful statements is a learnable skill based on finding the right contrast, not just having clever content.

Chapter 13.

This chapter emphasizes how to move from copying epigrams to creating them yourself. Key points include:

1: The creation of epigrams involves the coming together of two elements:

-

- The events that happen to you every day (opportunities)

- The inventory of words, phrases, and meanings in your brain (raw materials)

2: Why memorization doesn’t work:

-

- There are thousands of different situations you encounter

- No “Dictionary of Ready-Made Epigrams” could cover all possibilities

- You need creativity, not memorization

3: Teaching creativity through search-commands:

-

- Instead of providing answers, the focus is on teaching questions

- The mind scans specific memory areas when given these commands

- The process is like a search party looking for a lost child – systematically scanning areas

4: The importance of search-commands for instant retorts:

-

- You can’t prepare responses in advance for unpredictable statements

- But you can prepare the search-command: “Use contrast!”

5: Examples of spontaneous wit using contrast:

-

- W.C. Fields: “Yes, young ones. Parboiled.” (contrasting “like children” with “like food”)

- Parliament members: “Not, sir, as long as I am alive.” (contrasting “my own worst enemy” with “I am your worst enemy”)

- Oscar Wilde to Whistler: “You will, James. You will.” (contrasting “had said that” with “will say that”)

- Gertrude Stein’s final words: “Then what is the question?” (contrasting “answer” with “question”)

The chapter emphasizes that the key to spontaneous wit is having search commands ready to deploy, rather than trying to memorize specific responses for every situation.

Chapter 14.

This chapter introduces the second search-command: Implication. Key points include:

1: The importance of implication in delivering contrast:

-

- Contrast always appears below the surface of an epigram

- Part of the contrast remains unstated (implied)

- The audience must discover the final meaning themselves

2: Why directly stating the contrast fails:

-

- It telegraphs the punch, removing surprise

- It makes the thought too crude and too complete

- It gives the audience nothing to do

3: The complete process of constructing an epigram:

-

- Starting word/image is given (by audience or chosen by you)

- Search-command finds a contrast in your unconscious

- Second search-command finds words “one-step-removed” from the final image

- The audience completes the mental chain to reach the final image

4: Examples demonstrating the implication process:

-

- W.C. Fields: “Yes. Young ones. Parboiled.” (implies eating children without saying it directly)

- Parliament: “Not, sir, as long as I am alive.” (implies “I am your worst enemy” without stating it)

- Oscar Wilde: “You will, James. You will.” (implies “you will say it” without including “say it”)

5: The three parts of every epigram:

-

- Setting up the punch (can be done by you or another person)

- Throwing the punch (by implication)

- Landing the punch (when the audience figures out the implication)

6: The formula: “Contrast expressed by implication!”

The chapter emphasizes that the effectiveness of an epigram depends on letting the audience complete the mental process themselves, rather than explicitly stating the final image or contrast.

Chapter 15.

This chapter presents 12 tools for building implication into sentences to create powerful epigrams. Key points include:

1: Drop off the final image, letting the audience fill it in

-

- Example: “Ours is the age that is proud of machines that think, and suspicious of men who try to.”

2: Use Summary Words (it, this, that, these) to force redefinition of meaning

-

- Example: “When I was a boy, I was told anybody could become president; now I’m beginning to believe it.”

3: Give an outward symptom to imply an inward condition

-

- Example: “Life is like an onion; you peel off one layer at a time, and sometimes you weep.”

4: Switch the meaning of words between beginning and end

-

- Example: “The two most engaging powers of the author are to make new things familiar, and familiar things new.”

5: The super twist (taking readers on a mind trip with unexpected definition)

-

- Example: “Bureaucracy defends the status quo long past the time when the quo has lost its status.”

6: The surprise definition (redefining a word unexpectedly)

-

- Example: “My way of joking is to tell the truth. It’s the funniest joke in the world.”

7: The last-word contradiction (final word contradicts what came before)

-

- Example: “There is always an easy solution to every human problem — neat, plausible, and wrong.”

8: The pun (using word with double meaning)

-

- Example: “Man has made his bedlam; let him lie in it.”

9: Surprising use of opposites

-

- Example: “The girl who’s easy to get may be hard to take.”

10: Humorous repetition with slight change of meaning

-

- Example: “A committee is a group of the unprepared, appointed by the unwilling, to do the unnecessary.”

11: The bounce back (second half reflects the first)

-

- Example: “If you respect your job’s importance, it will return the favour.”

12: .Outright word contrast

-

- Example: “Take care of the means, and the end will take care of itself.”

The chapter emphasizes that these techniques can be combined and that the three fundamental rules of powerful epigrams are surprise, contrast, and implication.

Chapter 16.

This chapter presents 16 additional sentence strengtheners that give power to your communication, beyond implication techniques. Key points include:

1: Scan for boredom – Remove unnecessary words that block image-creation

2: Echo words (alliteration) – Use words that repeat the same first letters for melodic effect

-

- Example: “Spread sunshine, not shadow”

- Keep it subtle by placing non-alliterative words between alliterative ones

3: Parallel phrases – Echo structure for impact

-

- Example: “I kissed her. She slapped me.”

- Creates implication through action-reaction structure

4: Split-apart synonyms – Use words typically considered synonyms to express opposite ideas

-

- Creates pause, confusion, and ultimately deeper understanding

5: Metaphor – Use one universe of action to see more deeply into another

-

- Don’t use “like” for stronger impact (say “the ship ploughed through the water” not “the ship went through water like a plough”)

6: Vocabulary shift – Move between different sub-languages (sense language, thought language, etc.)

-

- Example: “Evolution has a cruel way of dealing with its failed mechanisms. It eats them.”

7: Metaphor chains – Follow a metaphor through multiple sentences, but limit to 2-3 extensions

8: Word juxtaposition – Place words next to each other that don’t typically belong together

-

- Example: “enslaved God” or “cruel charity”

9: Edit for sharpness – First get ideas down, then cut unnecessary words and strengthen structure

10: Memory devices – Help readers remember through:

-

- Punch

- Echo

- Metaphor

- Parallelism

- Steps in the ladder

- Markings

11: Borrow truth – Equate complicated ideas with simpler ones that work the same way

-

- Example: “Running a country is like running a marriage. You can’t build it on lies.”

12: Sentence-expanding clauses – Express complex ideas while maintaining clarity

-

- Keep each clause uninterrupted for immediate understanding

13: Hooks – Create incomplete sentences containing unstated questions that pull readers forward

-

- Example: “I have a problem” (makes reader wonder what the problem is)

14: Picture yourself debating – Imagine reader objections and strengthen your arguments accordingly

15: Focus on beginnings and endings – They’re remembered most, so make them powerful

16: Make words transparent – Readers should see through words to the images beneath

-

- “Write powerfully, not prettily”

- “Words disappear. Thoughts endure, and change the future.”

The chapter emphasizes that these techniques should be practiced regularly to become natural parts of your communication toolkit.

Understanding Brilliance Breakthrough

(Questions & Exercises)

Core Questions to Deepen Your Understanding.

- Picture Words vs. Abstract Words: Can you identify the difference between how your mind processes “celebration” versus “the birthday party with colourful balloons”? Which creates a more immediate mental image?

- Connector Word Awareness: Have you noticed how your mind processes differently when reading “The dog chased the ball” versus “Because the dog chased the ball”? How does the connector word change your expectation?

- Sentence Momentum: When you read a long, flowing sentence that carries you forward, what physical sensation do you notice? Does your breathing change? Do you feel a sense of anticipation?

- Implication Power: Think about a time when someone let you reach a conclusion yourself versus telling you directly. Which had more impact? Why might this principle apply to writing?

- Transparency Experience: Can you recall reading something so engaging you forgot you were reading? What made the author’s technique “transparent”?

Practical Exercises to Apply the Principles

Exercise 1: Picture Word Transformation

Take a paragraph from your current writing project and highlight all abstract nouns (concepts, ideas, qualities). Now rewrite replacing each with specific picture words that create immediate mental images.

Example:

- Before: “The implementation of the strategy led to significant improvement.”

- After: “The team pinned the new sales map to the wall, and within weeks, orders filled the inbox.”

Exercise 2: Connector Word Mastery

Write a short paragraph about any topic, but deliberately use these connector words to begin sentences: and, but, because, if, when, while. Notice how each creates a different relationship with what came before.

Example:

“The market shifted dramatically. And companies scrambled to adapt. But some leaders saw opportunity instead of crisis. Because they had prepared for volatility. When others panicked, they expanded.”

Exercise 3: Contrast Creation

Take any concept you need to explain and write it two ways:

- Without intentional contrast

- With deliberate contrast between elements

Example:

- Without contrast: “Our software offers many features including data analysis, reporting, and integration capabilities.”

- With contrast: “While other tools drown you in complicated data, our software transforms numbers into decisions.”

Exercise 4: Implication Practice

Write three sentences about your product/service/idea. Then rewrite each to remove the final conclusion, letting the reader complete the thought.

Example:

- Direct: “This approach saves you time and increases your productivity.”

- Implication: “This approach gives you back two hours every day…”

Exercise 5: Sentence Momentum

Take a choppy paragraph with many short sentences. Rewrite it using Schwartz’s principles of sentence momentum—varying sentence length, using parallel structures, and creating forward movement.

Example:

- Choppy: “We offer a solution. It helps businesses. They can grow faster. They can reduce costs. They become more efficient.”

- Momentum: “We offer a solution that helps businesses grow faster, reduce costs, and transform operations from labour-intensive to effortlessly efficient.”

Exercise 6: Transparency Test

Write a paragraph about something you’re passionate about. Then read it aloud and notice: Are you aware of the words themselves, or do they fade away letting the ideas shine through? Revise until the language becomes invisible.

Reflection Questions to Deepen Practice

- After doing these exercises, which principle creates the most noticeable change in your writing?

- When you read your writing aloud, where do you feel yourself stumble? Those are often places where picture words or better connector words could help.

- Which of your current writing projects could most benefit from the “dropping off final images” technique, and why?

- How might you use contrast more deliberately in your next important piece of writing?

- What habitual abstract words do you rely on that could be replaced with picture words?

Picture Words and the Five Senses in The Brilliance Breakthrough

The Sensory Foundation of Brilliant Writing

In The Brilliance Breakthrough, Schwartz elevates picture words beyond simple visualization. He recognizes that truly powerful communication engages all five senses to create a complete experiential reality for the reader. When we activate multiple sensory channels in our writing, we bypass abstract processing and connect directly with the reader’s experiential memory.

The Multi-Sensory Picture Word Approach

Schwartz argues that picture words work because they tap into how our brains naturally process information. Our earliest and most powerful memories aren’t stored as concepts—they’re stored as sensory experiences. By using words that trigger these sensory channels, we create what he calls “direct mind-to-mind communication.”

Visual Picture Words

Visual picture words form the foundation, but Schwartz distinguishes between different levels of visual specificity:

- Generic visual: “car” (creates a basic image, but lacks specificity)

- Specific visual: “red 1967 Mustang convertible” (creates immediate detailed image)

- Action visual: “the Mustang skidded around the corner” (adds motion to the image)

- Contextual visual: “the Mustang skidded around the rain-slicked corner as lightning flashed overhead” (places image in environment)

Schwartz emphasizes that specific visual details activate the reader’s visual cortex more completely than generic terms. The more specific the visual detail, the more neural regions engage in processing.

Auditory Picture Words

Sound words create what Schwartz calls “inner hearing”—the brain’s ability to simulate sounds even when reading silently. He identifies several categories:

- Natural sounds: rustled, crackled, thundered, whispered

- Mechanical sounds: clanged, whirred, screeched, hummed

- Voice qualities: rasped, bellowed, murmured, stammered

- Rhythmic sounds: pulsed, throbbed, thumped, drummed

Schwartz suggests that auditory words create a particularly powerful immediacy because sound alerts the primitive brain to both danger and opportunity. When we read “the door creaked open,” we don’t just see a door—we hear it, and that sound creates emotional response.

Tactile Picture Words

According to Schwartz, touch words engage the reader’s somatosensory cortex—the brain region that processes physical sensations. Categories include:

- Temperature: scorching, frigid, lukewarm, clammy

- Texture: rough, silky, jagged, velvety

- Pressure: crushed, caressed, squeezed, stroked

- Pain/pleasure: stinging, soothing, throbbing, tingling

What makes tactile words particularly powerful is their direct connection to emotional states. When we read “the icy wind bit through his thin jacket,” we physically simulate that sensation, activating emotional responses associated with cold and discomfort.

Olfactory and Gustatory Picture Words

Smell and taste words tap into what Schwartz calls our “chemical senses”—the most primal and emotionally connected senses. These include:

- Smell categories: pungent, fragrant, acrid, aromatic

- Taste categories: bitter, sweet, tangy, Savory

- Combined sensations: mouth-watering, nose-wrinkling, stomach-turning

Schwartz notes that smell and taste words have an unparalleled ability to trigger emotional memories because the olfactory bulb connects directly to the amygdala and hippocampus—brain regions involved in emotion and memory. When we read “the yeasty aroma of fresh bread filled the kitchen,” many readers experience immediate positive emotional associations.

The Sense Ratio Technique

One of Schwartz’s less-known but powerful techniques is what he calls the “sense ratio”—deliberately varying which senses you engage and in what proportion. He suggests:

- For high-energy scenes: emphasize sound, motion, and sharp visual details

- For emotional intimacy: emphasize smell, taste, and touch

- For intellectual clarity: emphasize clean, precise visual images with minimal other sensory input

The key insight is that different sensory combinations create different psychological effects. A paragraph rich in tactile and olfactory words creates intimacy, while one dominated by sharp visual and auditory words creates alertness and engagement.

The Sensory Bridge Technique

Another Schwartz technique is creating what he calls “sensory bridges”—transitioning from one sensory mode to another to guide the reader’s experience. For example:

“The glossy brochure caught her eye. As she flipped through the pages, the subtle scent of high-quality ink reached her. Her fingers traced the embossed logo while the promise of ‘financial freedom’ whispered in her mind.”

This passage moves deliberately from visual to olfactory to tactile to auditory, creating a complete sensory journey that feels natural rather than technical.

Experiential Exercise: Sensory Writing Practice

Schwartz recommends this exercise for developing your sensory writing abilities:

1: Choose an ordinary object (coffee mug, pen, book)

2: Spend 2 minutes experiencing it with each sense in turn:

-

- Look at it from different angles, in different lights

- Listen to sounds it makes when manipulated

- Feel its weight, texture, temperature

- Smell it (directly or indirectly)

- Taste it (if appropriate) or imagine its taste

3: Write one sentence for each sensory experience

4: Combine into a paragraph that creates a complete sensory experience

The Sensory Shorthand Principle

One of Schwartz’s most brilliant insights is what he calls “sensory shorthand.” He discovered that you don’t need extensive sensory descriptions to create powerful experiences. Often, a single well-chosen sensory detail activates the reader’s entire experiential memory.

For example, rather than describing an entire beach scene, the phrase “the gritty feeling of sand between her toes” might activate the reader’s complete beach experience—including sounds of waves, smell of salt air, and visual memories of shorelines.

Sensory Contrast for Maximum Impact

Schwartz emphasizes using sensory contrast to create impact. When you juxtapose opposing sensory experiences, both become more vivid:

“The silky chocolate melted on her tongue as the bitter coffee cut through its sweetness.”

“His whisper barely reached her ears above the thundering crowd.”

“In the sterile, white-tiled hospital room, a single crimson rose bloomed in a clear vase.”

These contrasts create what Schwartz calls “sensory tension”—a subtle but powerful way to maintain reader engagement.

Reflection Questions

- When you think about your most vivid memories, which senses dominate those experiences? How might you incorporate those same sensory channels in your writing?

- Look at a recent piece of your writing. Which senses did you engage? Which did you neglect entirely?

- Consider a concept you find difficult to explain. How might translating it into multi-sensory experiences make it more accessible?

- Which sensory channel do you naturally favour in your writing? Which feels most challenging to incorporate?

- How might you use the “sensory bridge” technique to create a more complete experience for your readers?

Eugene Schwartz’s Use of Picture Words in Direct Response Copy

The Sensory Approach in Schwartz’s Work

In The Brilliance Breakthrough, Schwartz emphasises the power of picture words – concrete words that create immediate mental images – over abstract concepts. His approach to direct response copywriting consistently applied this principle.

Concrete vs. Abstract in Persuasive Writing

Schwartz taught that effective copy transforms abstract benefits into concrete sensory experiences. This wasn’t just theory – it was fundamental to his approach to breakthrough advertising.

The Picture Word Principle in Practice

Schwartz advocated for writing that creates immediate mental images. When describing products or their effects, he recommended using words that engage the senses rather than conceptual terms.

For instance, rather than talking about “effective pain relief” (abstract), he would describe specific sensory experiences like “walking up stairs without wincing” (concrete visual and kinaesthetic image).

Before and After Scenarios

One technique Schwartz used was creating sensory-rich before and after scenarios that let readers experience the transformation rather than just understand it intellectually.

Making Benefits Tangible

Schwartz taught that benefits should be presented through concrete, sensory language so readers could experience them mentally before making a purchase.

The Importance of Specificity

In The Brilliance Breakthrough, Schwartz emphasizes the power of specific details over general claims. This specificity principle extended to his approach to direct response copy – making abstract promises concrete through specific sensory details.

NLP Language Patterns in Eugene Schwartz’s Brilliance Breakthrough

The Brilliance Breakthrough focuses on several language patterns that align with what would later be called NLP (Neuro-Linguistic Programming) techniques. While Schwartz didn’t use NLP terminology specifically, his patterns focus on how language affects mental processing and response. Here are the key patterns he teaches:

Picture Words vs. Abstract Words

Pattern: Concrete sensory-based language versus conceptual language

Explanation: Schwartz emphasizes using words that create immediate mental images rather than abstract concepts. When readers encounter picture words, their brains process them by creating sensory representations, making the communication more immediate and impactful.

Application: Replace abstract terms with concrete sensory descriptions whenever possible. Instead of “productivity improvement,” use “finishing your work by 3pm and walking out the door while others remain hunched over their desks.”

Connector Words as Transitional Hooks

Pattern: Using linguistic connectors to create relationships between ideas

Explanation: Schwartz emphasizes how words like “and,” “but,” “because,” “if,” “when,” and “while” create specific relationships between ideas and maintain momentum. He teaches that these words set up psychological expectations that keep readers engaged.

Application: Begin sentences with connector words to maintain flow and establish logical relationships between ideas. This creates what Schwartz calls “mental momentum” – the reader’s mind naturally follows the path created by these connectors.

Implication and Presupposition

Pattern: Embedding assumptions within statements rather than making claims directly

Explanation: Schwartz teaches embedding information within sentence structures in ways that cause readers to accept certain premises without directly stating them. By presupposing certain facts, you bypass potential resistance.

Application: Instead of claiming “This is the best solution,” use “When you experience how quickly this solution works, you’ll understand why so many people recommend it” – which presupposes that it works quickly and that many people recommend it.

Sentence Momentum and Rhythm

Pattern: Varying sentence length and structure to create rhythmic momentum

Explanation: Schwartz explains how alternating between short, punchy sentences and longer, flowing ones creates a rhythm that maintains attention and engagement. This rhythm affects how information is processed and retained.

Application: Follow a longer, detail-rich sentence with a short, impactful one. The contrast creates emphasis and maintains attention. Schwartz demonstrates how this creates a “verbal music” that keeps readers engaged.

Paired Opposites (Contrast Frames)

Pattern: Juxtaposing contrasting ideas to highlight differences

Explanation: Schwartz teaches creating sharp contrasts between opposing states or situations. This heightens perception of differences and creates clarity through comparison.

Application: Present the problem state in one sentence, then immediately contrast it with the solution state. This magnifies the perceived difference and creates what Schwartz calls “experiential voltage.”

Implied Causation

Pattern: Creating cause-effect relationships that link desired outcomes to specific actions

Explanation: Schwartz shows how to structure sentences to imply causation between taking a specific action and experiencing a desired result, even when the relationship isn’t explicitly stated as causative.

Application: Structure sentences to create implied cause-effect relationships: “People who read this book find themselves writing more persuasively within days” implies the reading causes the improvement without directly claiming it.

Sensory-Specific Language

Pattern: Using language that triggers specific sensory systems (visual, auditory, kinaesthetic)

Explanation: Schwartz teaches writing in ways that activate specific sensory channels. He explains how different sensory predicates (words associated with specific senses) trigger different processing in the reader’s mind.

Application: Match sensory language to the experience being described. For physical products, emphasize visual and tactile language. For services that create emotional states, use more kinaesthetic terminology.

Future Pacing

Pattern: Placing the reader mentally into a future scenario where they’ve already received benefits

Explanation: Schwartz demonstrates how to use language that projects readers into future scenarios where they’re already experiencing the benefits of a product or service, creating a “pre-experience” of satisfaction.

Application: Use present tense language to describe future scenarios: “You’re opening the package and immediately noticing how the weight feels in your hands…”

Pace and Lead Transitions

Pattern: Meeting readers where they are before guiding them where you want them to go

Explanation: Schwartz teaches acknowledging the reader’s current state or belief before transitioning to new information or perspectives. This creates rapport before introducing persuasive elements.

Application: Begin with statements that align with the reader’s known experience before transitioning to new information: “You know how frustrating it is when… Well, what if instead you could…”

These patterns form the foundation of Schwartz’s approach to clear, persuasive communication in The Brilliance Breakthrough. While he didn’t use NLP terminology, these patterns align with what would later be formalized in NLP practice, showing Schwartz’s intuitive understanding of how language affects mental processing and persuasion.